Gurupurinma

As we have Father’s Day and Mothers Day, Gurus also have their own day. This day is Gurupūrṇimā and it marks the anniversary of Veda Vyāsa, who occupies an exalted place in the hierarchy of teachers. Although there were also gurus for Veda Vyāsa, we look upon Vyāsa as the one who forms a link between the teachers that we know and the teachers that we don’t know. On this particular day, Gurupūrṇimā, the sannyāsins make a vrata, a vow, to stay in one place and teach for two months. Gurupūrṇimā occurs at the beginning of the rainy season in India, during which time one finds many small insects and other tiny creatures on the ground. Although sannyāsins usually wander from place to place, during the rainy season they remain in one place. At the time of taking sannyāsa, they took a vow of ahimsā, or non-injury to any living being, thus, the sannyāsins do not travel during the rainy season, in order to avoid killing any of the small creatures that might be in their path. For two months, beginning on Gurupūrṇimā day, they stay in one place and teach. Traditionally, the one place in which the sannyāsins stay is located on land between two bodies of water—streams, rivers, or canals. If they need to walk, they confine their movement to that area.

The vow is called the “four-month vow”, cāturmāsya-vrata. How does four months become two? There is a version of this vow that requires remaining stationary only for two lunar months, because the month is defined as a fortnight (pakṣa), the fifteen-day period of waxing or waning of the moon—pakṣo vai māsaḥ iti cāturmāsyam, “A month is indeed a pakṣa, thus, a four-month [vow].” For the two months of August and September the sannyāsins stay in one place and teach.

At the beginning of these two months, on this particular day called Gurupūrṇimā, they invoke the lineage of teachers, guruparaṃparā. All the gurus in the tradition, paraṃparā, especially in maṭhas, traditional monastic places of learning, are invoked. There are many maṭhas, including the Sankara maṭhas. The head of each maṭha is like a pontiff, and has a certain following. Each one of these heads performs a daily pūjā to invoke the gurus in the hierarchy. There are at least 16 gurus in the paraṃparā, and the grace of each is invoked in a water vessel. That is the ritual aspect of it. Just as we have Father’s Day and Mother’s Day, this day is Guru’s Day.

The word ‘guru’ has a number of meanings. The one who teaches is a guru; the one who helps somebody out of trouble is also a guru. These days, the word ‘guru’ is also used in the English language. In the American press we find ‘guru’ being used very widely by journalists. They say, for instance, “He is an automobile guru”, or “He is a stock market guru.” Even in India, it is used in that way. When I was a boy, I wanted to learn a very complex form of martial arts in which a stick is used. It is an excellent discipline that teaches coordination and other skills. One of our family’s agricultural workers was a teacher of this art. When I asked him to teach me, he said that first I had to give him the traditional offering to the teacher (gurudakṣiṇā). So I gave him a coconut, fruits, flowers, and a small amount of money. Only then would he begin teaching. His respect for his art was so great that he called himself a guru, and I respected him as such. When a person thinks of himself as a guru, the one who learns from him also feels that is true—he evokes in you the feeling of a disciple. In addition to martial arts teachers, classical dance masters and musicians also insist on being called gurus. Many teachers of art forms that must be taught directly are considered gurus.

While I have nothing against that, the word ‘guru’ really can be used only for a person who teaches spiritual knowledge. A guru is one who unfolds the knowledge that you are the whole, not separate from the Lord. A guru is the upadeśa-kartā—the one who is the teacher of the mahākvākya, the equation revealing that you are the whole. The wholeness which you are seeking basically is not separate from you. The very fact that you are seeking that is because it is you—you want to be yourself. And the one who teaches that is called a guru. That is the final definition: mahākvākya-upadeśa-kartā, the one who teaches the statement revealing the identity of the individual and the Lord, the whole.

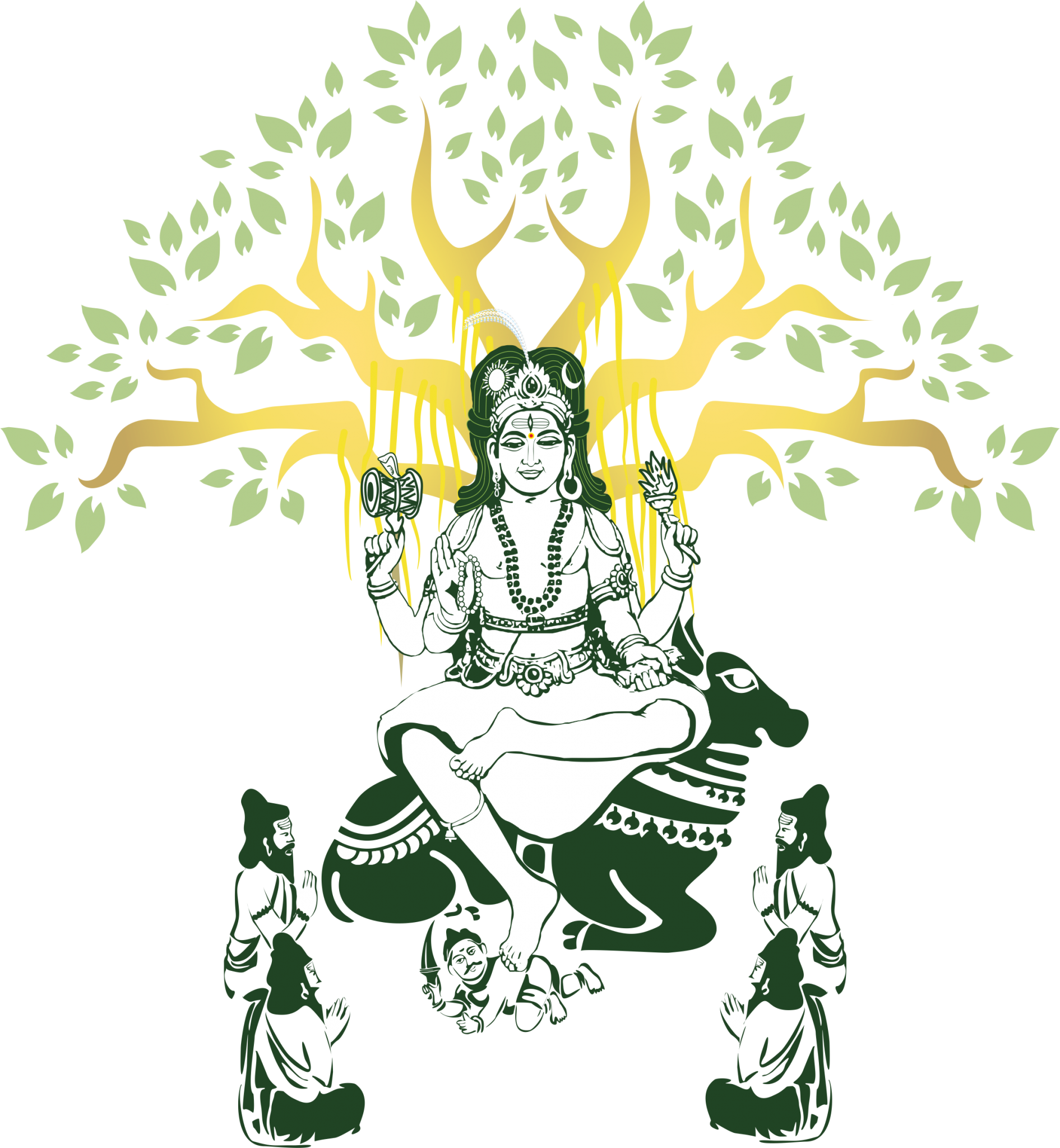

The guru is a human being. When the guru is praised, however, gurur brahma gurur viṣṇuḥ gurur devo maheśvaraḥ, “The guru is Brahma, the guru is Viṣṇu, the guru is Śiva,” the human element is not taken into account. Only the truth element is taken into account because the guru teaches that you are Brahman, you are limitless. When he teaches that you are limitless, he doesn’t mean, “I am limited; you are limitless.” You are limitless and he is limitless. And the limitless is Brahman; the limitless is Viṣṇu; the limitless is Rudra, or Śiva, the limitless is you. Everything is this limitlessness. So, when we praise the guru, the human element is just completely absorbed in the total element. You relegate the human element to the background, or you absorb it into the total. It is the total that is worshipped. In that way, the guru, the person with a human body who teaches, becomes a kind of an altar of worship. But what is being invoked is the Lord. Just as when you worship the form (mūrti) of Dakṣiṇāmūrti in the temple, it is not the mūrti you are worshipping, but the Lord. You invoke and worship the Lord in a particular form. Similarly, when you praise the person who teaches you and for whom you have sraddhā, it is not the individual person you praise, but the teaching itself, for what he teaches is not separate from him.

gururbrahma gurur viṣṇuḥ gururdevo maheśvaraḥ

guruḥ sākṣāt paraṃbrahma tasmai śrīgurave namaḥ

The guru is Brahma, the guru is Viṣṇuḥ the guru is Maheśvara (Śiva)

the guru is the immediate limitless Brahman.

Salutations to that revered guru.

Praise of the guru is praise for the truth of the teaching.

akaṇḍamandalākāram vyāptam yena carācaram

tatpadaṃ darśitaṃ yena tasmai śrīgurave namaḥ

yena- by whom; darśitaṃ – was shown; tat-padaṃ – that end; yena- by whom; vyāptam – is pervaded; akaṇḍa-mandala-ākāram – this entire universe; cara-acaram – of living beings and inert things; tasmai śrīgurave – unto that guru namaḥ – my salutations.

By whom was shown that end by whom this entire universe of living beings and inert things is pervaded, unto that guru my salutations.

Tasmai śrīgurave namaḥ —unto that guru, my namaskāra, my salutation; tadpadaṃ darśitaṃ yena, by whom that padam, that end, that abode, was shown very clearly, darśitaṃ. And what is that padam? yena padena carācaram vyāptam. Here, pada is Brahman. By which (yena) Brahman, by which reality, this entire universe (akaṇḍamandalākāram) of living beings and inert things (carācaram) are pervaded (vyāptam). To that teacher (tasmai śrīgurave), by whom (yena) that Lord, that vastu, that reality (tatpadaṃ), who is in the form of this great universe, was shown (darśitaṃ), my namaskāra (namaḥ).

The gaining of any knowledge is the greatest miracle. How is the mind able to grasp a totally new fact or concept? If you are ignorant by nature, you cannot know. If you are knowing by nature, you need not know. And you cannot see more than you know, yet you keep increasing your existing knowledge; you keep on shedding ignorance. That is because under certain conditions you are able to see. The teacher is the one who creates those conditions. He has to create the necessary inner conditions for knowledge to take place, and he does so by using reason and by citing your own experiences. In that way, he helps you see. In fact, the teacher creates a condition from where you cannot but see. That’s what teaching is about. And it’s a miracle, an impossibility that happens. You cannot see more than you already know, yet you always do. That’s how you keep knowing more and more. How can that happen? The answer is very simple: you are all- knowing.

Your essence is pure knowledge. We say that the Lord is all-knowing, that all knowledge is in the Lord. Yet who is this Lord? If the Lord were to say, “I am the Lord,” that “I am” is not going to be any different from the meaning of the statement “I am” that you make. When you say, “I am,” that is exactly the same as the “I am” of the Lord. There is one limitless consciousness. Consciousness cannot be limited because it is one, and it is formless. The Lord is a conscious being, and the limitless consciousness is the same for the Lord and for you. I am limited only with reference to my body, mind and sense organs. As consciousness I am limitless. The Lord ‘also’ is limitless consciousness, for being limitless, there is only one consciousness. If the Lord is all-knowing, that all-knowledge rests in that consciousness. Which consciousness? The consciousness that is one, that is limitless, that is you. And that means all knowledge rests in you.

If all knowledge rests in me, why don’t I know everything? With reference to the individual, the knowledge is inhibited. With reference to the Lord, it is uninhibited. This inhibiting factor is what we call āvaraṇa, something that covers knowledge. When we create the conditions for knowledge to take place, the āvaraṇa goes. That āvaraṇa, that ignorance, that veiling power goes, so that knowledge is unveiled. Interestingly, the English word that refers to any new finding is ‘dis-covery’—dispelling the cover, dismissing the cover. Whether intentionally coined in that way or not, the word is amazingly apt. The cover is the veil— āvaraṇa. Knowledge need only be uncovered, discovered, because it is already there. You don’t really know anything on your own. All knowledge is only from the Lord, whether it is knowledge of how to make an enchilada or knowledge of physics. Every form of knowledge is in the all-knowledge. And the removal of the inhibiting factor is what we call knowing. Like a surgeon who removes cataracts so that you can see the world, the guru creates the conditions for ignorance to be dispelled, so that you can see the truth of yourself and the world.

There are two types of blindness. One is not repairable; the other is. This second type of blindness is pointed out in the following verse as an example.

ajñānatimirāṇḍhasya jnāñāñjanaśalākhayā

cakṣurūnmilitaṃ yena tasmai śrīgurave namaḥ

tasmai śrīgurave namaḥ – to that guru my salutations. yena – by whom; cakṣuḥ – the eye ( of knowledge); unmilitaṃ – is opened; ajñāna-timira-aṇḍhasya- for the one who is blind due to ignorance; jnāña-añjana-śalākhayā – by applying the ointment of knowledge.

My salutations to that guru by whom the eye ( of knowledge) is opened for the one who is blind due to ignorance by applying the ointment of knowledge.

Here the example is a blind person, andha. What is the cause of the blindness? Timira—cataracts. Due to cataracts, the person is not able to see; he is timira-aṇḍha. What is to be done? The surgeon removes the cataracts. In India, in the days in which this verse was composed, they seem to have had a remedy in the form of an ointment to remove cataracts. Añjāna means ointment. Añjana-śalākhayā—by applying this ointment, the malady was removed. So too, here, even though you are a knowing person, essentially an all-knowing person, that knowledge is covered by ignorance. But, like a cataract, the ignorance can be removed. Therefore, everybody is ajñāna-timira-aṇḍha, blind due to the cataract of ignorance. Ignorance alone is the cataract; because of that cataract, one becomes blind, ajñānam eva timiraṃ timireṇa andhaḥ bhavati. This ignorance alone is the timira, the cataract, because of which, knowledge is inhibited. That inhibiting factor is removed by whom? To that one (tasmai) by whom (yena) the inner eye of knowledge (cakṣuḥ) is opened (unmilitaṃ), my namaskāra (namaḥ). Therefore, the guru does not really ‘deliver’ anything. He is the one who removes; he is the surgeon who removes that inhibiting factor and helps you see. It is a highly responsible job and it can only be done by one who knows the truth and the method of teaching. If the teacher doesn’t know, he will only confuse others with his words.

A teaching method is required because the problem is a very peculiar one. In one book it is said that the guru must be a person with a little extra compassion. Ordinary compassion is not enough. An ordinarily compassionate human being will feel empathy when he sees a person who is really suffering, and may begin helping that person in whichever way he can. That is natural human compassion. But if he sees someone suffering for no reason at all, empathy-born compassion will not be evoked. It is through the gate of empathy that compassion and the desire to help are evoked. Since a person who suffers for no reason may not evoke empathy, it takes someone with extra compassion to choose to help that person. You can help a person who suffers for a reason by taking measures to remove the cause of the suffering, but how can you help a person who suffers for no reason? He is like the ajñāna-sarpadaṣṭa, the person who mistakenly believes he has been bitten by a snake. If he were really bitten by a snake, you could help him by taking him to the hospital for an anti-venom injection. And perhaps you could administer first aid by tying a piece of cloth above the bite and making an opening for the poisoned blood to escape. These are the practical steps that you could take, all of which are induced by your empathy. But what can you do for the ajñāna-sarpadaṣṭa when he screams, “Help! Help! I’ve been bitten by a snake!” When asked where he was bitten, he points in the direction of his foot, saying, “There!” He refuses to even look in the direction of what he feels to be a deadly wound. But when you look at his foot, you see only a thorn lodged there, which you remove. “Do you feel better now?” you ask. “No, no!” he cries. “I was bitten by a snake!” In fact, what had happened was that he stepped on a thorn and at the same time, he looked down near his foot and saw a water hose. In his panic, the hose became a snake, and the thorn became its deadly fangs. Now the fellow is showing all the effects of fear—he really is sweating, his heart is really pounding—and he may even die of fright, all due to his belief, “I was bitten by the snake!” True or not, since he thinks so, it is true for him. Yet knowing that he is not in danger, you can’t help but feel some amusement, rather than empathy. So, how will you help this person? Since there is no danger, you could walk away, but still, you see how he is suffering. That’s why an extra ounce of compassion is required. That compassion comes from the realization, “I was once like that; I went through that experience, too.” If I had gone through the same blessed thing, I can easily appreciate the person’s lot and I can be of help. That is why the guru is described as ahetuka dayasindhuh—an ocean of daya, compassion, without any reason. There is no reason. The student may ask, “Why you are so compassionate? Why should you teach me at all? What have I done?” Nothing. “What do you expect of me?” Nothing. You ask why I teach you. Why should I not teach you? You need to be taught, so I teach.

This knowledge is not like a discrete academic subject that you can learn simply by reading a textbook. It is a complete unfoldment and the teacher-student connection is necessary in order to make the knowledge work for the student. It is similar to a relationship with a therapist in which trust and a certain amount of time are necessary. The guru is more like a super-therapist. He must re-orient the student over a period of time, directly or indirectly, so the student sees through ingrained self-beliefs. But what makes the extraordinary difference is that the guru is also the one who opens up your heart and gives you an insight about yourself, a self that is totally acceptable. There is no other relationship that will do that.

In experiential love, you are given that kind of feeling, because when somebody says “I love you,” you feel totally, unconditionally accepted. Everything about you is accepted—your height, your nose, your mind. That experience gives you an inner opening to see that you are acceptable, at least to one other person. But that is not real self- acceptance because it is based on the other’s approval of you. You think you are okay because the other person says, “I love you.” The approval does not come through your own eyes but from the eyes of the other. And later on, you both discover a lot of things about each other that are not acceptable at all. Then you find you are adding clauses to “I love you.” “I love you…even though”. “I’d be happy loving you if you could…get up a little earlier…if you stopped snoring…if you could think a little differently…if you were not a Republican.” Afterwards, we tack on conditions, and thus, the unconditional acceptance that I need is not gained through the eyes of others. Yet, since I do not feel totally acceptable in my own eyes, I go on seeking it in the eyes of others.

That is why it is so very important to have an insight about yourself as totally lovable and acceptable. That is what the guru does—he helps you see yourself as lovable. He frees you. Then that vision is yours, and you become a source of love to everyone else. That’s why the guru-śiṣya relationship is entirely different from an ordinary relationship and why the guru is given so much praise in the śāstra and in the tradition.

So, Gurupūrṇimā is a very important day for all seekers. On this Guru’s Day we seek the blessings of all the gurus in the paraṃparā, in the tradition, remembering that the final guru is Lord Dakṣiṇāmūrti, the source of all knowledge. And so, we praise him. We worship him, seeking the grace of the guru.

As we have Father’s Day and Mothers Day, Gurus also have their own day. This day is Gurupūrṇimā and it marks the anniversary of Veda Vyāsa, who occupies an exalted place in the hierarchy of teachers. Although there were also gurus for Veda Vyāsa, we look upon Vyāsa as the one who forms a link between the teachers that we know and the teachers that we don’t know. On this particular day, Gurupūrṇimā, the sannyāsins make a vrata, a vow, to stay in one place and teach for two months. Gurupūrṇimā occurs at the beginning of the rainy season in India, during which time one finds many small insects and other tiny creatures on the ground. Although sannyāsins usually wander from place to place, during the rainy season they remain in one place. At the time of taking sannyāsa, they took a vow of ahimsā, or non-injury to any living being,thus, the sannyāsins do not travel during the rainy season, in order to avoid killing any of the small creatures that might be in their path. For two months, beginning on Gurupūrṇimā day, they stay in one place and teach. Traditionally, the one place in which the sannyāsins stay is located on land between two bodies of water—streams, rivers, or canals. If they need to walk, they confine their movement to that area.The vow is called the “four-month vow”, cāturmāsya-vrata. How does four months become two? There is a version of this vow that requires remaining stationary only for two lunar months, because the month is defined as a fortnight (pakṣa), the fifteen-day period of waxing or waning of the moon—pakṣo vai māsaḥ iti cāturmāsyam, “A month is indeed a pakṣa, thus, a four-month [vow].” For the two months of August and September the sannyāsins stay in one place and teach.At the beginning of these two months, on this particular day called Gurupūrṇimā, they invoke the lineage of teachers, guruparaṃparā. All the gurus in the tradition, paraṃparā, especially in maṭhas, traditional monastic places of learning, are invoked. There are many maṭhas, including the Sankara maṭhas. The head of each maṭha is like a pontiff, and has a certain following. Each one of these heads performs a daily pūjā to invoke the gurus in the hierarchy. There are at least 16 gurus in the paraṃparā, and the grace of each is invoked in a water vessel. That is the ritual aspect of it. Just as we have Father’s Day and Mother’s Day, this day is Guru’s Day.The word ‘guru’ has a number of meanings. The one who teaches is a guru; the one who helps somebody out of trouble is also a guru. These days, the word ‘guru’ is also used in the English language. In the American press we find ‘guru’ being used very widely by journalists. They say, for instance, “He is an automobile guru”, or “He is a stock market guru.” Even in India, it is used in that way. When I was a boy, I wanted to learn a very complex form of martial arts in which a stick is used. It is an excellent discipline that teaches coordination and other skills. One of our family’s agricultural workers was a teacher of this art. When I asked him to teach me, he said that first I had to give him the traditional offering to the teacher (gurudakṣiṇā). So I gave him a coconut, fruits, flowers, and a small amount of money. Only then would he begin teaching. His respect for his art was so great that he called himself a guru, and I respected him as such. When a person thinks of himself as a guru, the one who learns from him also feels that is true—he evokes in you the feeling of a disciple. In addition to martial arts teachers, classical dance masters and musicians also insist on being called gurus. Many teachers of art forms that must be taught directly are considered gurus.While I have nothing against that, the word ‘guru’ really can be used only for a person who teaches spiritual knowledge. A guru is one who unfolds the knowledge that you are the whole, not separate from the Lord. A guru is the upadeśa-kartā—the one who is the teacher of the mahākvākya, the equation revealing that you are the whole. The wholeness which you are seeking basically is not separate from you. The very fact that you are seeking that is because it is you—you want to be yourself. And the one who teaches that is called a guru. That is the final definition: mahākvākya-upadeśa-kartā, the one who teaches the statement revealing the identity of the individual and the Lord, the whole.

As we have Father’s Day and Mothers Day, Gurus also have their own day. This day is Gurupūrṇimā and it marks the anniversary of Veda Vyāsa, who occupies an exalted place in the hierarchy of teachers. Although there were also gurus for Veda Vyāsa, we look upon Vyāsa as the one who forms a link between the teachers that we know and the teachers that we don’t know. On this particular day, Gurupūrṇimā, the sannyāsins make a vrata, a vow, to stay in one place and teach for two months. Gurupūrṇimā occurs at the beginning of the rainy season in India, during which time one finds many small insects and other tiny creatures on the ground. Although sannyāsins usually wander from place to place, during the rainy season they remain in one place. At the time of taking sannyāsa, they took a vow of ahimsā, or non-injury to any living being,thus, the sannyāsins do not travel during the rainy season, in order to avoid killing any of the small creatures that might be in their path. For two months, beginning on Gurupūrṇimā day, they stay in one place and teach. Traditionally, the one place in which the sannyāsins stay is located on land between two bodies of water—streams, rivers, or canals. If they need to walk, they confine their movement to that area.The vow is called the “four-month vow”, cāturmāsya-vrata. How does four months become two? There is a version of this vow that requires remaining stationary only for two lunar months, because the month is defined as a fortnight (pakṣa), the fifteen-day period of waxing or waning of the moon—pakṣo vai māsaḥ iti cāturmāsyam, “A month is indeed a pakṣa, thus, a four-month [vow].” For the two months of August and September the sannyāsins stay in one place and teach.At the beginning of these two months, on this particular day called Gurupūrṇimā, they invoke the lineage of teachers, guruparaṃparā. All the gurus in the tradition, paraṃparā, especially in maṭhas, traditional monastic places of learning, are invoked. There are many maṭhas, including the Sankara maṭhas. The head of each maṭha is like a pontiff, and has a certain following. Each one of these heads performs a daily pūjā to invoke the gurus in the hierarchy. There are at least 16 gurus in the paraṃparā, and the grace of each is invoked in a water vessel. That is the ritual aspect of it. Just as we have Father’s Day and Mother’s Day, this day is Guru’s Day.The word ‘guru’ has a number of meanings. The one who teaches is a guru; the one who helps somebody out of trouble is also a guru. These days, the word ‘guru’ is also used in the English language. In the American press we find ‘guru’ being used very widely by journalists. They say, for instance, “He is an automobile guru”, or “He is a stock market guru.” Even in India, it is used in that way. When I was a boy, I wanted to learn a very complex form of martial arts in which a stick is used. It is an excellent discipline that teaches coordination and other skills. One of our family’s agricultural workers was a teacher of this art. When I asked him to teach me, he said that first I had to give him the traditional offering to the teacher (gurudakṣiṇā). So I gave him a coconut, fruits, flowers, and a small amount of money. Only then would he begin teaching. His respect for his art was so great that he called himself a guru, and I respected him as such. When a person thinks of himself as a guru, the one who learns from him also feels that is true—he evokes in you the feeling of a disciple. In addition to martial arts teachers, classical dance masters and musicians also insist on being called gurus. Many teachers of art forms that must be taught directly are considered gurus.While I have nothing against that, the word ‘guru’ really can be used only for a person who teaches spiritual knowledge. A guru is one who unfolds the knowledge that you are the whole, not separate from the Lord. A guru is the upadeśa-kartā—the one who is the teacher of the mahākvākya, the equation revealing that you are the whole. The wholeness which you are seeking basically is not separate from you. The very fact that you are seeking that is because it is you—you want to be yourself. And the one who teaches that is called a guru. That is the final definition: mahākvākya-upadeśa-kartā, the one who teaches the statement revealing the identity of the individual and the Lord, the whole. The guru is a human being. When the guru is praised, however, gurur brahma gurur viṣṇuḥ gurur devo maheśvaraḥ, “The guru is Brahma, the guru is Viṣṇu, the guru is Śiva,” the human element is not taken into account. Only the truth element is taken into account because the guru teaches that you are Brahman, you are limitless. When he teaches that you are limitless, he doesn’t mean, “I am limited; you are limitless.” You are limitless and he is limitless. And the limitless is Brahman; the limitless is Viṣṇu; the limitless is Rudra, or Śiva, the limitless is you. Everything is this limitlessness. So, when we praise the guru, the human element is just completely absorbed in the total element. You relegate the human element to the background, or you absorb it into the total. It is the total that is worshipped. In that way, the guru, the person with a human body who teaches, becomes a kind of an altar of worship. But what is being invoked is the Lord. Just as when you worship the form (mūrti) of Dakṣiṇāmūrti in the temple, it is not the mūrti you are worshipping, but the Lord. You invoke and worship the Lord in a particular form. Similarly, when you praise the person who teaches you and for whom you have sraddhā, it is not the individual person you praise, but the teaching itself, for what he teaches is not separate from him.

The guru is a human being. When the guru is praised, however, gurur brahma gurur viṣṇuḥ gurur devo maheśvaraḥ, “The guru is Brahma, the guru is Viṣṇu, the guru is Śiva,” the human element is not taken into account. Only the truth element is taken into account because the guru teaches that you are Brahman, you are limitless. When he teaches that you are limitless, he doesn’t mean, “I am limited; you are limitless.” You are limitless and he is limitless. And the limitless is Brahman; the limitless is Viṣṇu; the limitless is Rudra, or Śiva, the limitless is you. Everything is this limitlessness. So, when we praise the guru, the human element is just completely absorbed in the total element. You relegate the human element to the background, or you absorb it into the total. It is the total that is worshipped. In that way, the guru, the person with a human body who teaches, becomes a kind of an altar of worship. But what is being invoked is the Lord. Just as when you worship the form (mūrti) of Dakṣiṇāmūrti in the temple, it is not the mūrti you are worshipping, but the Lord. You invoke and worship the Lord in a particular form. Similarly, when you praise the person who teaches you and for whom you have sraddhā, it is not the individual person you praise, but the teaching itself, for what he teaches is not separate from him.gururbrahma gurur viṣṇuḥ gururdevo maheśvaraḥ guruḥ sākṣāt paraṃbrahma tasmai śrīgurave namaḥ

The guru is Brahma, the guru is Viṣṇuḥ the guru is Maheśvara (Śiva)

the guru is the immediate limitless Brahman.

Salutations to that revered guru.

Praise of the guru is praise for the truth of the teaching.akaṇḍamandalākāram vyāptam yena carācaram

tatpadaṃ darśitaṃ yena tasmai śrīgurave namaḥ

yena- by whom; darśitaṃ – was shown; tat-padaṃ – that end; yena- by whom; vyāptam – is pervaded; akaṇḍa-mandala-ākāram – this entire universe; cara-acaram – of living beings and inert things; tasmai śrīgurave – unto that guru namaḥ – my salutations.By whom was shown that end by whom this entire universe of living beings and inert things is pervaded, unto that guru my salutations.Tasmai śrīgurave namaḥ —unto that guru, my namaskāra, my salutation; tadpadaṃ darśitaṃ yena, by whom that padam, that end, that abode, was shown very clearly, darśitaṃ. And what is that padam? yena padena carācaram vyāptam. Here, pada is Brahman. By which (yena) Brahman, by which reality, this entire universe (akaṇḍamandalākāram) of living beings and inert things (carācaram) are pervaded (vyāptam). To that teacher (tasmai śrīgurave), by whom (yena) that Lord, that vastu, that reality (tatpadaṃ), who is in the form of this great universe, was shown (darśitaṃ), my namaskāra (namaḥ).The gaining of any knowledge is the greatest miracle. How is the mind able to grasp a totally new fact or concept? If you are ignorant by nature, you cannot know. If you are knowing by nature, you need not know. And you cannot see more than you know, yet you keep increasing your existing knowledge; you keep on shedding ignorance. That is because under certain conditions you are able to see. The teacher is the one who creates those conditions. He has to create the necessary inner conditions for knowledge to take place, and he does so by using reason and by citing your own experiences. In that way, he helps you see. In fact, the teacher creates a condition from where you cannot but see. That’s what teaching is about. And it’s a miracle, an impossibility that happens. You cannot see more than you already know, yet you always do. That’s how you keep knowing more and more. How can that happen? The answer is very simple: you are all- knowing.Your essence is pure knowledge. We say that the Lord is all-knowing, that all knowledge is in the Lord. Yet who is this Lord? If the Lord were to say, “I am the Lord,” that “I am” is not going to be any different from the meaning of the statement “I am” that you make. When you say, “I am,” that is exactly the same as the “I am” of the Lord. There is one limitless consciousness. Consciousness cannot be limited because it is one, and it is formless. The Lord is a conscious being, and the limitless consciousness is the same for the Lord and for you. I am limited only with reference to my body, mind and sense organs. As consciousness I am limitless. The Lord ‘also’ is limitless consciousness, for being limitless, there is only one consciousness. If the Lord is all-knowing, that all-knowledge rests in that consciousness. Which consciousness? The consciousness that is one, that is limitless, that is you. And that means all knowledge rests in you.If all knowledge rests in me, why don’t I know everything? With reference to the individual, the knowledge is inhibited. With reference to the Lord, it is uninhibited. This inhibiting factor is what we call āvaraṇa, something that covers knowledge. When we create the conditions for knowledge to take place, the āvaraṇa goes. That āvaraṇa, that ignorance, that veiling power goes, so that knowledge is unveiled. Interestingly, the English word that refers to any new finding is ‘dis-covery’—dispelling the cover, dismissing the cover. Whether intentionally coined in that way or not, the word is amazingly apt. The cover is the veil— āvaraṇa. Knowledge need only be uncovered, discovered, because it is already there. You don’t really know anything on your own. All knowledge is only from the Lord, whether it is knowledge of how to make an enchilada or knowledge of physics. Every form of knowledge is in the all-knowledge. And the removal of the inhibiting factor is what we call knowing. Like a surgeon who removes cataracts so that you can see the world, the guru creates the conditions for ignorance to be dispelled, so that you can see the truth of yourself and the world.There are two types of blindness. One is not repairable; the other is. This second type of blindness is pointed out in the following verse as an example.ajñānatimirāṇḍhasya jnāñāñjanaśalākhayā

cakṣurūnmilitaṃ yena tasmai śrīgurave namaḥ

tasmai śrīgurave namaḥ – to that guru my salutations. yena – by whom; cakṣuḥ – the eye ( of knowledge); unmilitaṃ – is opened; ajñāna-timira-aṇḍhasya- for the one who is blind due to ignorance; jnāña-añjana-śalākhayā – by applying the ointment of knowledge.My salutations to that guru by whom the eye ( of knowledge) is opened for the one who is blind due to ignorance by applying the ointment of knowledge.Here the example is a blind person, andha. What is the cause of the blindness? Timira—cataracts. Due to cataracts, the person is not able to see; he is timira-aṇḍha. What is to be done? The surgeon removes the cataracts. In India, in the days in which this verse was composed, they seem to have had a remedy in the form of an ointment to remove cataracts. Añjāna means ointment. Añjana-śalākhayā—by applying this ointment, the malady was removed. So too, here, even though you are a knowing person, essentially an all-knowing person, that knowledge is covered by ignorance. But, like a cataract, the ignorance can be removed. Therefore, everybody is ajñāna-timira-aṇḍha, blind due to the cataract of ignorance. Ignorance alone is the cataract; because of that cataract, one becomes blind, ajñānam eva timiraṃ timireṇa andhaḥ bhavati. This ignorance alone is the timira, the cataract, because of which, knowledge is inhibited. That inhibiting factor is removed by whom? To that one (tasmai) by whom (yena) the inner eye of knowledge (cakṣuḥ) is opened (unmilitaṃ), my namaskāra (namaḥ). Therefore, the guru does not really ‘deliver’ anything. He is the one who removes; he is the surgeon who removes that inhibiting factor and helps you see. It is a highly responsible job and it can only be done by one who knows the truth and the method of teaching. If the teacher doesn’t know, he will only confuse others with his words.A teaching method is required because the problem is a very peculiar one. In one book it is said that the guru must be a person with a little extra compassion. Ordinary compassion is not enough. An ordinarily compassionate human being will feel empathy when he sees a person who is really suffering, and may begin helping that person in whichever way he can. That is natural human compassion. But if he sees someone suffering for no reason at all, empathy-born compassion will not be evoked. It is through the gate of empathy that compassion and the desire to help are evoked. Since a person who suffers for no reason may not evoke empathy, it takes someone with extra compassion to choose to help that person. You can help a person who suffers for a reason by taking measures to remove the cause of the suffering, but how can you help a person who suffers for no reason? He is like the ajñāna-sarpadaṣṭa, the person who mistakenly believes he has been bitten by a snake. If he were really bitten by a snake, you could help him by taking him to the hospital for an anti-venom injection. And perhaps you could administer first aid by tying a piece of cloth above the bite and making an opening for the poisoned blood to escape. These are the practical steps that you could take, all of which are induced by your empathy. But what can you do for the ajñāna-sarpadaṣṭa when he screams, “Help! Help! I’ve been bitten by a snake!” When asked where he was bitten, he points in the direction of his foot, saying, “There!” He refuses to even look in the direction of what he feels to be a deadly wound. But when you look at his foot, you see only a thorn lodged there, which you remove. “Do you feel better now?” you ask. “No, no!” he cries. “I was bitten by a snake!” In fact, what had happened was that he stepped on a thorn and at the same time, he looked down near his foot and saw a water hose. In his panic, the hose became a snake, and the thorn became its deadly fangs. Now the fellow is showing all the effects of fear—he really is sweating, his heart is really pounding—and he may even die of fright, all due to his belief, “I was bitten by the snake!” True or not, since he thinks so, it is true for him. Yet knowing that he is not in danger, you can’t help but feel some amusement, rather than empathy. So, how will you help this person? Since there is no danger, you could walk away, but still, you see how he is suffering. That’s why an extra ounce of compassion is required. That compassion comes from the realization, “I was once like that; I went through that experience, too.” If I had gone through the same blessed thing, I can easily appreciate the person’s lot and I can be of help. That is why the guru is described as ahetuka dayasindhuh—an ocean of daya, compassion, without any reason. There is no reason. The student may ask, “Why you are so compassionate? Why should you teach me at all? What have I done?” Nothing. “What do you expect of me?” Nothing. You ask why I teach you. Why should I not teach you? You need to be taught, so I teach.This knowledge is not like a discrete academic subject that you can learn simply by reading a textbook. It is a complete unfoldment and the teacher-student connection is necessary in order to make the knowledge work for the student. It is similar to a relationship with a therapist in which trust and a certain amount of time are necessary. The guru is more like a super-therapist. He must re-orient the student over a period of time, directly or indirectly, so the student sees through ingrained self-beliefs. But what makes the extraordinary difference is that the guru is also the one who opens up your heart and gives you an insight about yourself, a self that is totally acceptable. There is no other relationship that will do that.In experiential love, you are given that kind of feeling, because when somebody says “I love you,” you feel totally, unconditionally accepted. Everything about you is accepted—your height, your nose, your mind. That experience gives you an inner opening to see that you are acceptable, at least to one other person. But that is not real self- acceptance because it is based on the other’s approval of you. You think you are okay because the other person says, “I love you.” The approval does not come through your own eyes but from the eyes of the other. And later on, you both discover a lot of things about each other that are not acceptable at all. Then you find you are adding clauses to “I love you.” “I love you…even though”. “I’d be happy loving you if you could…get up a little earlier…if you stopped snoring…if you could think a little differently…if you were not a Republican.” Afterwards, we tack on conditions, and thus, the unconditional acceptance that I need is not gained through the eyes of others. Yet, since I do not feel totally acceptable in my own eyes, I go on seeking it in the eyes of others.That is why it is so very important to have an insight about yourself as totally lovable and acceptable. That is what the guru does—he helps you see yourself as lovable. He frees you. Then that vision is yours, and you become a source of love to everyone else. That’s why the guru-śiṣya relationship is entirely different from an ordinary relationship and why the guru is given so much praise in the śāstra and in the tradition.So, Gurupūrṇimā is a very important day for all seekers. On this Guru’s Day we seek the blessings of all the gurus in the paraṃparā, in the tradition, remembering that the final guru is Lord Dakṣiṇāmūrti, the source of all knowledge. And so, we praise him. We worship him, seeking the grace of the guru.